Gareth Liddiard is at the eye of the fuckstorm

The former Drones frontman has been cooking up something new.

Words Triana Hernandez | Photos Morgan Hickinbotham | November 2017

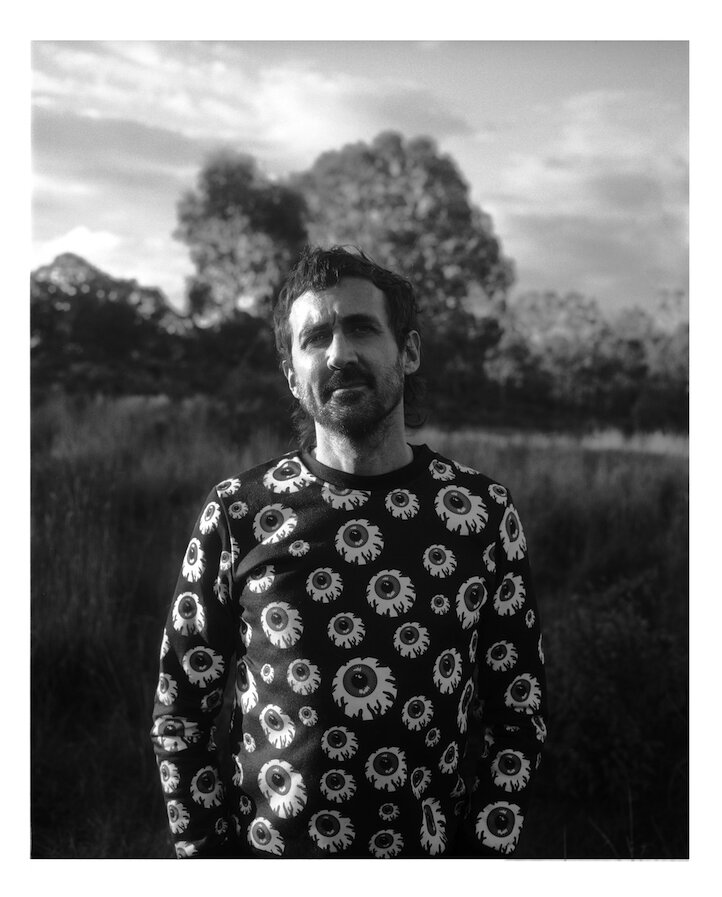

Gareth Liddiard pictured at home in regional Victoria for Swampland 03. Photo: Morgan Hickinbotham.

Gareth Liddiard sits in front of me talking with such ease and calm that it makes the lines on his face look pleased, like they’re proud to be there. It’s just past midday and we drink beers and bloody marys and joke about being responsible adults. The large, unpretentious cafe he has picked sits humbly in the middle of Melbourne’s CBD, unintimidated by the surrounding rows of skyscrapers.

As the frontman of the Drones, Liddiard is renowned as one of Australia’s most innovative contemporary musicians. He is an eccentric composer and warped lyricist with songs that oscillate between laments about the modern human condition and mockeries of Australia’s special brand of neoliberal, colonial, often redneck culture.

In 1997, the Drones moved from Perth to Melbourne to pursue their musical ambitions. Over the next two decades, they toured the world, met most of their musical idols, shared stages with Neil Young and Patti Smith, and released seven albums.

Since 2013, Liddiard and Drones bassist Fiona Kitschin have been making music from the depths of a rural town a couple of hours from Melbourne. Away from the belly of the beast, last year the band released Feelin Kinda Free, an album that embraces a more electronic, noise-experimental path.

This year Liddiard and Kitschin started Tropical Fuck Storm, which also features Lauren Hammel (High Tension) on drums and Erica Dunn (Harmony and Palm Springs) on guitar. When we met in June, the band were still in the early stages of writing material, but Liddiard described the new project passionately—alluding to a hectic, funky, borderline anarchic nature; a sonic continuation of where the Drones left off. The future looks exciting for the band as Liddiard’s dreams are never lukewarm.

As I set up the recorder, I ask him how he feels about interviews and he says they are “like a weird form of therapy”. He sips a beer and smiles expectantly, showing off impish dimples; he giggles like a kid—excited and eager.

When you look back at your career, what do you reckon has been the number one source of inspiration for your music?

I don’t know why, but I’ve always had a penchant for depressing, dark music. There were hits when I was growing up like “I’m Walking on Sunshine” and I hated it—it was a waste of three minutes. Then in 1975 my family and I moved to London and I started listening to the bands that were top of the charts there, like Pink Floyd’s The Wall. There was also Blondie and the Clash. These bands were depressing, dark or angry and I loved it. My parents would be like, “What’s wrong with him?” But I just thought it was the best shit.

In the late ’70s there would’ve been a lot of “happy” music like Bee Gees, Olivia Newton John and John Travolta blasting on the radio.

Yeah. I felt like there was this kind of alternative movement going on around the same time, though. There was the start of punk, there was the Clash, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin. All of these bands had relatively intense songs, it wasn’t “party” music, it was heavier songs and minor chords. So anyway, I’m not sure exactly how it worked on me, I feel like it’s a chicken-and-egg situation. Did I start liking emotionally heavy music because I was already a relatively depressed kid or did I turn into a musician with dark and heavy compositions because I liked that kind of music? I’m not sure.

When you sit down to write a song, where do you look for these dark or intense emotions?

Anywhere. When you need them, you just have to find them. I started playing in bands and, you know, the singer was shit, so I had to sing, and the bass player was shit, so I started doing the bass, the guitar player was shit so, anyway, what I’m trying to say is that I started songwriting out of necessity. When I sing I need to find words to say. I just need something to sing.

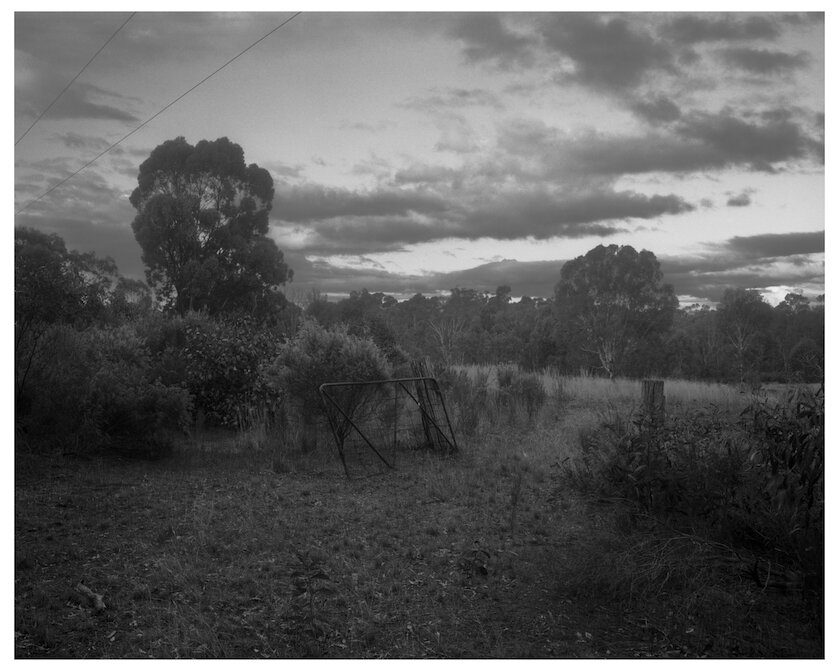

Photo: Morgan Hickinbotham.

Where do you find that “something” to sing about? I’ve read in a lot of your interviews that you reference books, psychology, the news, history—but, I wonder, how often do you write directly about yourself?

I’d say each song is fifty per cent directly autobiographical and the other fifty per cent is stuff that’s assembled from lots of miscellaneous different places—but it’s all mostly from real life just simply because it would be too hard to think that shit up. For example, the other day we were talking about what I See Seaweed is about and I was saying it’s sort of like a buried psychological trip. It’s about buried psychology, it’s about everyone carrying shit around and not dealing with things, or pushing things down.

Everyone has that in common, so I used that as a kind of base but then cherry-picked bits about my housemate, bits about me, there’s bits about my best friend. I’m like a magpie that just grabs shit from everywhere.

Do you actually like writing lyrics?

No. I hate writing lyrics. It’s really hard. You gotta work with something that’s not really there. You have to fill in an empty space with words and you gotta make it good. It would be easy to fill a space with crap, but it has to be good. It’s so much pressure and it’s hard to experiment, unlike instruments or sounds. I only write lyrics, and also sing, out of necessity. Even when singing I have limitations because I feel like I mumble a lot and I have a fucked- up jaw from being smacked in the head so I can’t open my mouth very wide.

You are renowned for your emotion-fuelled performances. How do you feel about live shows?

I’m not the world’s biggest extrovert and my job is stupid. You just get up and there’s just a bunch of people staring at you and you just babble and tell them how you feel and you are the most important person in the room—that’s just stupid and I don’t always feel great about it. So I guess that’s the physicality element of performing because if I did all that just standing still then I would feel like an idiot. So if you get revved up and you get physical about it, then you can feel like a different person and you can feel confident.

So when you are standing on stage you are kinda wishing you weren’t there?

I move past that point quickly. The physical element helps because once it takes off it’s just like being on autopilot and I don’t have to worry about it anymore, I can concentrate on playing my instruments and singing. I guess I mostly just disconnect. It all just becomes this really emotionally internal thing and I have to balance it out with the elements of dexterity and elements of going berserk. There’s also lots of energy spent on regulating how berserk I go because otherwise I’ll exhaust myself during the first songs. It’s a lot like running an emotional marathon.

After almost twenty years performing, how do you keep your shows so emotionally fresh?

You basically just need to not die. I feel like early on I had a reasonably emotional life and I’ve got fuel forever. From my early teens to around the age of twenty-seven I had a lot of shit go horribly badly. I also feel like I have enough of a personality disorder to catch all that in. I think I’m immature enough and narcissistic enough to be a musician but not enough for it to be damaging to me or others. But definitely enough to make me be that idiot that gets on stage with a guitar like, “Hey, check out what I thought today.” It’s silly and weird.

“We grew up in the ’90s. Now, self-promotion as a musician is totally acceptable and so is talking about wanting to make coin. Back then, people equated poverty with good music. ”

Let’s talk about the Drones. After seven records, numerous awards and consistent praise from the media, did you still feel nervous about the reception Feelin Kinda Free would get when it was released last year?

Yes. It’s annoying. Every time you finish a record you don’t go, “Oh, they are going to love this,” you always think, “They are going to think this is shit.”

So how do you know when an album is ready?

I don’t know; that’s an interesting question. I mean, you have to please yourself. You have to think, “That’s cool. That’s sorted.” But at the same time you are just bored with it because you have listened to it a million times. It’s complicated. That’s why recording albums is weird, you are kinda living this strange dual life. A part of you wants to be liked and a part of you is thinking, “Fuck them,” and another part is just sick of the whole thing. I mean ultimately you go, “Yeah, everyone will hate this but fuck them because they are stupid.” So I guess you got to be cocky to make something like this in the first place.

After decades of writing albums though, what’s been an important lesson in knowing how to deal with that kind of duality?

I suppose just knowing that you need to trust a version of yourself from the past. What I mean is, normally when you start a song you start with a strong vision and then a month or so later you are bored of it because you are listening to it all the time and working on it. But you just have to keep going and trust yourself from a month ago. You have to put your board down and finish your song. It’s draining but also fun.

The Drones have been one of the longest-running successful bands in Australia to come from the underground into the mainstream and keep fans and critics in awe album after album. How have you managed to keep the band afloat and not sink ship?

Fuck knows. Fi’s good at her job. We’re not shit— we’re never completely shit—but then again, there’s plenty of bands who are shit and have had careers for ages. I guess we must fill a niche and be useful.

I think anything that lasts the test of time lasts as long as it’s useful. If you can have a song that moves people, whether it’s doing that on the day it’s made or doing that twenty or fifty years later, it’s because it’s still moving people and it’s got a use—people wanna hear it. I guess we’ve been useful somehow to people.

Speaking of Fiona, she’s the second-longest-serving member of the Drones and she’s also been a part of every studio album recorded. What do you think Fiona has consistently brought to the band throughout the years?

As far as musicality goes, she’s just amazing with the simple basslines, which comes from influences like the Birthday Party or Suicide. If it wasn’t for her keeping it simple we might’ve got too expensive and expansive with the band and then we probably wouldn’t be as good. Also, she manages us and she’s good at making decisions. If you ever think, “How does a noisy, yucky band become reasonably big?” It’s because of her. I suppose Fiona doesn’t get much credit for that because it’s all happening behind the scenes but she’s the one that somehow turned this into a small business.

Understanding the industry and knowing how to manage your own band is one of the biggest assets for anyone trying to make it. It’s no longer the ’70s where you can just be a good musician and that’s it, your label will do the rest for you.

Totally. It would be nice to think that you can be a consummate artist and earn a decent income, but the reality is you need to think about other things outside of music if you want to get to that point. I mean, it’s an interesting thing because times have changed.

We grew up in the ’90s and we weren’t allowed to make a living out of that shit. Now, self-promotion as a musician is totally acceptable and so is talking about wanting to make coin. Back then, people equated poverty with good music. People really resented bands like Fugazi for making money, or, “Kurt Cobain killed himself because he succeeded”. There’s a whole guilt-trip for musicians about that, but these days it’s fine to talk about wanting to make an income from your music.

Were the Drones open from the start about wanting to be a successful band?

I mean, we did move to from Perth to Melbourne to “make it” because we wanted to do music forever so we consciously decided to give it a proper go. In general, I feel like as a band we wanted it but we didn’t advertise it, that’s the thing. One of my favourite bands is Black Flag and you could say that from an outsider’s perspective they seemed all anti-aspirational, but in reality it was all about making a living from it. It was about being serious professionals—having a label and debts and all of that—but they couldn’t advertise it because people would think they were sellouts.

I guess it all worked out.

Yeah. I mean, we are not super successful. Our maximum sales have been like ten thousand copies for one album. Bands like Fugazi have three million per record or whatever. I do think being famous like Nick Cave would be really hard though—I wouldn’t want that. So, you know, it’s all about a nice balance.

“It’s going to be groovier. It’ll be like Fela Kuti—just endless rolling funk but more anarchic, more likely to go off the rails. ”

Let’s talk about your new project, Tropical Fuck Storm. I heard it’s got members from High Tension and Palm Springs.

It’s got Fiona, Lauren [Hammel] from High Tension and Erica [Dunn] from Harmony. Hammel is awesome, she’s just a fucking maniac drummer and I like maniac drummers. I saw High Tension about a year ago when she had just joined. I was like, “Fucking hell, check her out.” She just goes mental on the drums and we’re like, “Calm down!” I love it. She usually plays metal or punk and stuff like that, but that’s irrelevant because we’re not going to do that. We want to do something different.

What kind of music is it?

It’s early days, we’ve got six songs that aren’t completely finished, so it’s hard [to say]. I guess the only thing would be that it’s 2017, so let’s keep up—you know what I mean? Acoustic drums are great but then they’re hundreds of years old and there’s all this new stuff—electronic gear. I dunno, it’s always going to be a bit the same because it’s got me singing and that kind of thing. So it’s almost like the last Drones album; we go from there, but take it forward a bit more. It’s going to be groovier, it’ll be like Fela Kuti— just endless rolling funk but more anarchic; more likely to go off the rails.

You’ve created music almost exclusively with the Drones or on your own for a while now. What’s it like to write songs with totally new people?

It’s exciting because I really haven’t played with that many different people and to play with younger people is great because they have a lot of energy and a very different bunch of ideas to me and Fi.

You said before that you really hate writing lyrics but you are singing in this new band too?

Well, I don’t know any singers who would do it. I would love to be in a band where there’s a really good singer and I’m just the guitar player. I’m picky. I’m critical. I’m probably overly hyper-critical. I can’t find anyone to sing my songs, you know, the way I’d want them to be sung. I wish, though.

It seems like all your musical projects are ships where you’re the captain and you have a team of people who help you navigate it. Are you comfortable in saying you are the captain of these bands?

Yeah, totally. Captain of the ship. Team leader, if you wanna put it in business speak. I’m the one who goes, “Okay, we’re going here, let’s figure out how to do it,” and everyone’s like, “Yeah, alright.” I have the vision, I’m the visionary wanker. Or, perhaps I’m just an ideas guy and I need people to help me. I go, “Okay, I’ve been listening to this bunch of music— we can take all these elements. This is weird from this epoch of Russian history—let’s nick this from here, nick that from there and then these ideas, put them all together and mix them up, make it work.” It has to be a cohesive whole, it has to have oomph, it can’t pull punches. And then they all help me, whoever I’m working with, and it’s just a shitfight until we have that.

Are you going to be a musician for the rest of your life?

Yeah, I’m a full-timer. So many musicians are just doing it because they are at uni; they know one day they’ll get a “good job” and put music aside. I’m not that.

When was the moment you realised you’re not that?

Really early on when I was like four or some shit. I thought, “This is ridiculous,” seeing people work or watch TV.

You were four and you were like, “Look at these people; look at this society”?

Yeah, and then hearing Pink Floyd’s The Wall and hearing that “We don’t need no education” line and just going, “That’s right!” I remember school being this stupid fucking thing you had to do and I literally left school thinking, “That’s it, now I’m on holidays for the rest of my life. Occasionally I’ll have to work, but life, it’s like bits of free time, it’s a working holiday.” You know, the band was called the Drones because we’d be coming home at six or seven in the morning and we’d see people waiting at bus stops, men in suits going to work and they were the drones, so we thought, “Fuck that.”

So you’ve always wanted to be a musician, since then?

No, I just liked music. I didn’t think I could become a musician; I didn’t think I would ever play music. I used to get Casio keyboards when I was really little and rewire them, make all kinds of fucked up sounds. I also played with my sister’s tape recorder and my tape recorder doing weird stuff. I was just doing it because, “Oh, what happens when you do this?” I wasn’t doing it because I thought I’d be a musician. It didn’t occur to me. But then, a lot of things didn’t occur to me.

When did you start thinking of yourself as a musician?

When I was about twelve or thirteen I got a saxophone. I would go to the State Library in Perth, borrow tapes and whoever stocked the tape section was the craziest free jazz aficionado, so there was Thelonious Monk, Albert Ayler, Ornette Coleman and all the really freaky fucked up evil shit, so I just got all those cassettes and copied them all and got into that. I guess also Keith from Black Flag was a huge inspiration. He was a white guy who hated white guys and I thought, “That’s cool.” I started seeing myself as a musician. Then in school I started playing with a bunch of other people, but it was mostly rock’n’roll, so I sold the sax and I bought a bass guitar to join in and then sort of moved up like that. Before I knew it, I was twenty-four, moved from Perth to Melbourne to make the Drones a thing. [I] looked at Rui Pereira and I said, “We’re never going to stop doing this, are we?” Back then, I didn’t think, though. I just took drugs and played music, it’s all I ever did.

It seems like from a really young age you sort of surrendered yourself to music, devoted your time to it and eventually lived from it. Do you ever stop and think, “Why do I do this?”

It’s an internal thing. I was just a mega daydreamer. I failed high school because I was just looking out the window thinking about other things—music mostly. I didn’t like the outside world, so I was that guy looking inwards kind of thing. Music offered me that space, whether I was tweaking a keyboard or learning saxophone or guitar or anything, I could daydream and not be present. I didn’t want to be present. Then drugs were another great way to do that. When we discovered pot it was amazing, it was unbelievable.

So music-as-an-escapism-from-the-ugly-real-world kind of thing?

Yeah. I grew up on the beach in WA and there was a lot of surfers and they were really macho and music gave me an in with them. I would play with punk bands at parties and shit like that. I could be around them and under their wing, which was handy because they were big boys. The outside world was scary and fucked up and then you’d go into Perth and it was just guaranteed you’d get mugged, so I felt protected. So basically, I couldn’t surf, I was never sporty, I was too skinny, but thanks to music they let me in. It might’ve been different if I was thirty kilograms heavier and a surfer with pecs, capable of punching through the world—which is what they do. Music just helped to internalise my feelings, and the only time they ever came out was when I was playing, so it was a great way to let them out.

Photo: Morgan Hickinbotham.

It’s been almost two decades, seven albums and a lot of experimenting and evolving. When you look back at the discography, which ones feel the most emotionally pure?

I guess they all have a bit of that, so the question could be more like, “Which albums are the least self-conscious about doing that?” And to me, that’s the first three albums. Those albums were wanting to be anti-social, anti-music. Here Come the Lies is meant to be long and painful, it’s not meant to draw you in. We thought, “If we clear rooms, great.” Those albums were coming from us being young, boozed, on drugs. We had no idea what was going on, we were just partying and going berserk doing what we loved doing. In a way, I feel like we were fish in water, not realising we were in the water and some old fish would swim past and go, “Morning guys, how’s the water?” and we would be like “What water?”

How’s it different now that you’re older and know you’re “in water”?

I guess you have a sense of control. It’s cool. You enjoy getting to things in a calm manner rather than just rushing through. You become self-aware.

There’s that whole narrative that musicians are at their most creative when they are young, fucked up on alcohol and drugs. In retrospective, do you think this was the case for you?

Yes and no. Chaos is good but you need some quiet time to listen to what you got to say and write it down. I think as a young person there’s always upheaval and trauma and it’s a huge part of your life and you don’t really notice it until much later. When I started the Drones my best friend and bandmate was Rui Pereira who was a war refugee and had been through a lot of fucked up shit. I was also with my girlfriend who had a father with PTSD as a war veteran and all these fucked up things happened at home. So that was my little crew and we were all dealing with extreme trauma but, like I said, fish don’t understand the concept of water—they don’t understand it’s there.

I certainly didn’t understand it and that my interest in music was honed by all this. I mean, how could I know? We were having a good time and it all ended when my girlfriend died. The party hit a wall, but what I realise now is that the party wasn’t fuelled by drugs, it was fuelled by trauma.

I don’t think I’ve heard about this before, was this during the Drones?

I don’t talk about it much. Yes, it was right at the start of the Drones. When it happened, it galvanised who I am. There’s all this dumbarse mythology in guitar- based music that you have to go through the washer if you deserve the voice, but to me, after that happened, I just felt like I didn’t need to answer to anybody.

Did the Drones become therapy during those days?

It gave me something to put all that into. The Drones felt cathartic and therapeutic some days, but not always. What the Drones was, really, was that when we stopped taking drugs we still had an interest in life, we still had the band. Most drug addicts turn into squares when they quit, life becomes dull. We kept creating. Then Fiona came into the picture and joined the band and we were just a bunch of fuck-ups but it was great because we were having fun and we worked with a framework so it was healthy.

Compared to that level of emotional intensity from two decades ago, do you feel like becoming older and gaining financial and emotional stability makes it harder for your creative output?

Sometimes I do worry about it but then I think: we do have a house, but it’s rented. I do have an income but it’s not very big and it could go away in the next couple of years. We are still kind of hanging by a thread so there’s still a fair bit of anxiety. We don’t have superannuation or a back-up plan, there’s no security. But, in saying that, what you make is deeper than what situation you were in when you made it. I don’t think I’ll change who I am as I grow older. Maybe my metabolism will change and I will turn fat and get a beer gut and get old, but I don’t think my personality is going to change.

Will you be fifty and still be a musician with the right amounts of narcissism and immaturity?

Yeah [laughs]. I mean, I didn’t sign up to grow up. I don’t want to. I didn’t become a musician to grow up. I essentially left high school thinking, “That’s it, that’s the last time I do anything I don’t want to do,” and I’ve worked hard at it and managed to do that for the most of it—my life is a holiday.

This piece first appeared in Swampland issue three.